The Athenian revolution

Contents

In 508-507 BC, the people of Athens revolted and overthrew the ruling aristocratic oligarchy. After the revolution, Athens became a participatory democracy ruled by male free citizens. This rule lasted for almost a century.

Background

By the 7th century BC, Athens had begun suffering from a land and agrarian crisis, with widespread social unrest. Around them, many city-states in Greece were now ruled by tyrants who favoured sectional interests.

In Athens, the Athenian nobleman Cylon attempted to set himself up as a tyrant in 632 BC, but was repelled by the people of Athens and ultimately stoned to death. In order to restore order in the aftermath, the Areopagus appointed Draco replace the oral law system with a written legal code.

In 594 BC, Solon – the premier archon – issued reforms that gave each free resident male of Attica a political function. Through these reforms, political rights that had previously been limited to the aristocracy were extended to every free citizen of Athens who also fulfilled the property requirement. The Boule, a council of 400 men (100 from each of Athen´s four tribes) was established to run the daily affairs of Athens and set the political agenda. Solon also established an assembly that was open to all male citizens regardless of social class.

The reforms of Solon helped give stability to Athens, and gave the populace a taste for democracy. Yet, there was always the threat of tyranny. Eventually, Peisistratus carried out a successful populist coup and declared himself tyrant of Athens. He ruled for most of 561-527 BC, and was succeeded by his sons Hippias and Hipparchus. When Hipparchus was assassinated by two men who were against the tyrannous regime, Hippias became an even harsher tyrant who carried out many executions and imposed high taxes.

As the Athenian´s despise for Hippias grew, he sought military support from the Persians and entered into alliances with other Greek tyrants. Simultaneously, the Athenian aristocratic family Alcmaeonidae, who had been exiled from Athen by Peisistratus in 546 BC, began plotting how to depose the tyrant.

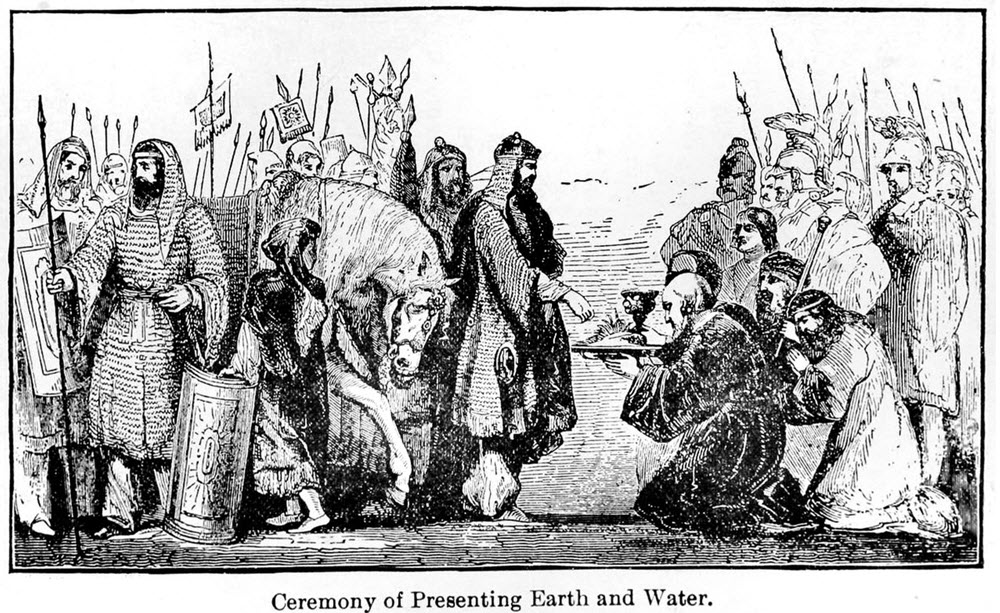

The Alcmaeonidae family managed to convince the Oracle of Delphi to recommend the Spartans to aid in an invasion of Athens. The Oracle was successful, and the invasion took place in 510 BC, headed by Cleomenes I of Sparta. Hippias was deposed and ousted, and the Spartan king put a pro-Spartan oligarchy in charge of Athens, headed by Isagoras.

Revolution

The Athenians were happy to be rid of Hippias, but not happy to be ruled by the Spartan-loyal oligarchs. Especially the lower and middle classes of Athenian society sought a return of the type of democracy that had existed before.

The Alcmaeonidae family was pro-democracy and against Isagoras, and Cleisthenes, one of their most prominent members, was therefore expelled from Athens by the oligarchs, who claimed that Cleisthenes was cursed. Isagoras next step was to dispose hundreds of other Athenians of their homes and expel them too, claiming that they too carried the curse.

(One of Cleisthenes forefathers was Megacles. Megacles was the eponymous archon of Athens in 632 BC when Cylon made an unsuccessful attempt to seize control of Athens. Megacles was convicted of killing Cylon supporters who had taken refuge on the Acropolis as suppliants of Athena. Since killing suppliants were against the law, Megacles and his family, the Alcmaeonids, were exiled from Athens and a miasma (stain / pollution), also known as the Cylonian curse, was put on them and their descendants.)

After the mass-expulsions, Isagoras and the oligarchs attempted another power-grab, which soon proved to be their undoing. They attempted to dissolve the Boule, but the council resisted and the Athenian populace rose up to defend the Boule. They revolved against Isagoras and the oligarchs, and this is known as the Athenian revolution.

Just like the Cylon supporters back in 632 BC, Isagoras, king Cleomenes I and their supporters fled to Acropolis. There, they stayed for two days, surrounded by enemy Athenians. On the third day, an agreement was made, which allowed Isagoras and Cleomenes to leave, but 300 of Isagora´s supporters were executed.

The Athenians called back the exiled Cleisthenes, together with hundreds of other exiles, and Cleisthenes was elected archon of Democratic Athens.

Aftermath

With Cleisthenes as archon, several reforms were carried out to solidify the Athenian democracy. Among other things, he reorganized society to decrease the power of the four traditional tribes, since they were the ones most likely to put forth another tyrant. The four tribes organized themselves along family lines, so Cleisthenes instead created a system based on ten tribes where tribal affiliation was rooted in geographical residency instead of than bloodline. Your area of residence was your deme, and your deme decided which tribe you belonged too.

Other notable changes:

- Patronymics were replaced with demonymics, i.e. family surnames were replaced by names that denoted ones deme.

- The sortition system was established, where citizens were randomly selected to fill government positions. (Previously, they had been filled based on kinship and heritage.)

- Members of the Boule had to swear an oath to advice according to the laws what was best for the people.

- The Boule was put in charge of proposing laws to the assembly of voters. The assembly of voters convened in Athens circa 40 times per year to vote on proposals. Proposals could be passed, rejected or returned to for amendments.

- The first known used of the ostracism system is from 487 BC. The intention of the ostracism system was to make it possible for citizens to vote to exile another citizen for 10 years, if the citizen was considered a threat to the democracy. Under this system, an exiled persons property was maintained, but he was not allowed to be physically present in the city.

This article was last updated on: February 8, 2022